Don’t promise the farm - unpicking the complex law of equitable estoppel

30 Mar 2025

Is a verbal promise binding?

A common question from our clients is whether a verbal promise is binding. Can they rely on and enforce a promise given orally?

The answer is ‘yes’; if certain conditions are met.

The recent High Court decision in the case of Kramer v Stone[1]demonstrates this in the context of an inheritance dispute.

This is a particularly important decision for economically wealthy Western Australia, given the vast intergenerational wealth transfer that is projected to take place in Australia over the next two decades, with around $5 trillion projected to be passed down — almost half of which is held by boomers and tied up in property, private businesses, family trusts and superannuation.[2]

Kramer v Stone

What began as a dispute over the inheritance of a family farm resulted in a landmark ruling by the High Court in Kramer v Stone.

This case concerns an oral promise made decades ago by a farm owner to a farm worker that the farm would pass to the worker upon the owner’s death. That promise was inconsistent with later wills made by the farm owner, which ultimately left the farm to her daughter.

The Court ruled that the verbal promise to the farm worker was binding, even though the farm owner did nothing further to encourage the worker to rely on the promise and the owner was not actually aware that the farm worker relied upon it.

In this article, we consider this case and the law of equitable estoppel.

Overview

The key facts are concisely set out in the first paragraph of the High Court’s judgement:

The… farm worker …earned an irregular and meagre income working on a farm as a “share farmer”, sharing some of the costs and income derived from the farm. The farm worker was made a promise by the owner of the farm that he would inherit the farm on the owner’s death. Without that promise, the farm worker would have terminated the share farming agreement, obtained employment that returned a much higher level of income, and enjoyed a new lifestyle free from some of the hardships endured on the farm. Instead, as the owner reasonably expected would occur, the farm worker relied upon the promise by continuing to live and work on the farm for another 23 years. But the owner did not leave the farm to the farm worker in her will, so when the owner died, the farm worker did not inherit the farm.

At the initial trial, the Supreme Court of New South Wales concluded that these circumstances gave rise to an “estoppel” against the deceased estate of the owner, requiring title to the farm to be held on trust for the farm worker.

The Court of Appeal agreed and upheld the decision.

The executors of the estate appealed to the High Court on the grounds that estoppel required:

1. Some act of encouragement by the promisor, after the promise is made.

So, in the case of Kramer, the farm worker would need to demonstrate that after the owner had promised to leave him the farm, the owner performed some further that encouraged of the farm worker to rely on the promise.

2. The promisor had actual knowledge that the person it was made to relied upon it.

In the case of Kramer, the executors argued that the farm worker needed to prove the owner was aware that the farm worker was relying on the promise, and that the farm worker would suffer a detriment if the promise was not fulfilled.

The High Court determined that neither of those matters is required to establish estoppel.

Although this case effectively confirmed the pre-existing legal test for estoppel remains unchanged, it clarifies some important matters concerning the law of estoppel more broadly, which we expect to see relied upon increasingly in inheritance disputes over the coming years.

Read on for a more detailed overview of the matter and key legal principles.

The facts

Dame Leonie and her husband, Dr Harry, owned a 100-acre farming property in the Colo Valley, New South Wales. They had two daughters, Hilary and Jocelyn.

David Stone worked on the farm as a share farmer for almost 40 years from 1975.

A dispute arose after the owners died and the farm was left to Hilary in Dame Leonie’s final will.

The farming agreements

From 1975, David had a close personal working relationship with Dame Leonie and Dr Harry. He initially worked under a simple share farming oral agreement with Dr Harry on the following terms:[3]

- David would grow crops and maintain the farm.

- Dr Harry would pay all operating costs except fuel, which would be a cost shared equally between Dr Harry and David.

- David would live rent-free in a house on the farm.

- David would receive a quarterly retainer of $600 and half of the gross proceeds from the sale of produce and cattle.

The amount of David’s quarterly retainer increased over time and the proportion of the liability for fuel and costs was varied in 1980 so that Dr Harry became liable for two-thirds of the fuel costs. But the agreement remained informal and either party could terminate it at will.

The promises

David was made three promises by the farm owners:[4]

- Dr Harry would give David a life interest in the farm, provided Dr Harry’s family would retain the use of the cottage on the farm.

- Dr Harry would leave the farm to Dame Leonie in his will, and Dame Leonie would leave the farm to David in her will, and he could “do whatever he wanted with it” provided Dame Leonie and Dr Harry’s two children, Hilary and Jocelyn, would have the use of the cottage.

- The third promise was made shortly after Dr Harry died in 1988, when Dame Leonie told David that she and Dr Harry had agreed that the farm would pass to David upon Dame Leonie’s death, together with a sum of money. David replied by thanking Dame Leonie.

Dame Leonie’s wills

In 1996 and 1999, around 8 and 11 years after the third promise, incomplete and unexecuted draft wills were prepared for Dame Leonie. Dame Leonie then executed wills in 2000, 2003, 2006, and 2011.

All of the unexecuted and executed wills contemplated or provided for David to receive a legacy only. The incomplete will in 1996 did not mention the farm. But from the time of the unexecuted will in 1999, the farm was to be bequeathed to Hilary and Jocelyn and later to Hilary only.

Dame Leonie was diagnosed with dementia in 2010 and died in 2016. In her final will, made on 11 November 2011, Dame Leonie left the farm to Hilary. The farm was valued at the time of the grant of probate in December 2016 at $1.5 million. David was left a gift of $200,000.

The earlier decisions

First instance trial

The trial judge found that the first promise had been superseded by the second and that the second promise, which was made by Dr Harry, could not have legal effect against Dame Leonie. Those findings were not challenged. Instead, the focus of the reasoning of the trial judge and the Court of Appeal was on the legal effect of Dame Leonie’s promise and David’s reliance upon it to his detriment.

The trial judge determined that an estoppel arose that entitled David “to appropriate equitable relief” and declared that in lieu of the provision of $200,000 for David in Dame Leonie’s will, the farm was held on trust for David by the executors of the estate of Dame Leonie.

The Court of Appeal

The executors of the estate of Dame Leonie appealed to the Court of Appeal on eight grounds, including that the trial judge made an error by concluding that it was sufficient to establish estoppel by encouragement that Dame Leonie ought reasonably to have assumed that part of David’s motivation for continuing to share farm was an expectation that he would inherit the farm. On this ground, the appellants submitted that an estoppel by encouragement required Dame Leonie to have had “subjective knowledge” that David had acted to his detriment.

This ground of appeal had two important legal aspects:

- an element of estoppel by encouragement required some encouragement or actual knowledge of detrimental reliance by Dame Leonie.

- the encouragement or actual knowledge of detrimental reliance be subsequent to Dame Leonie making the third promise.

The Court of Appeal unanimously dismissed this and all other grounds of appeal.

Appeal to High Court

The executors of the estate of Dame Leonie appealed the decision to the High Court of Australia, on the ground that the Court of Appeal made an error in its approach to an estoppel by encouragement by failing to establish further encouragement by Dame Leonie (the promisor) after the promise was made, and by failing to establish that Dame Leonie had actual knowledge of David’s (the promisee) reliance on the promise.

For the reasons set out below, the High Court did not accept either ground of appeal.

The law

The requirements of equitable estoppel

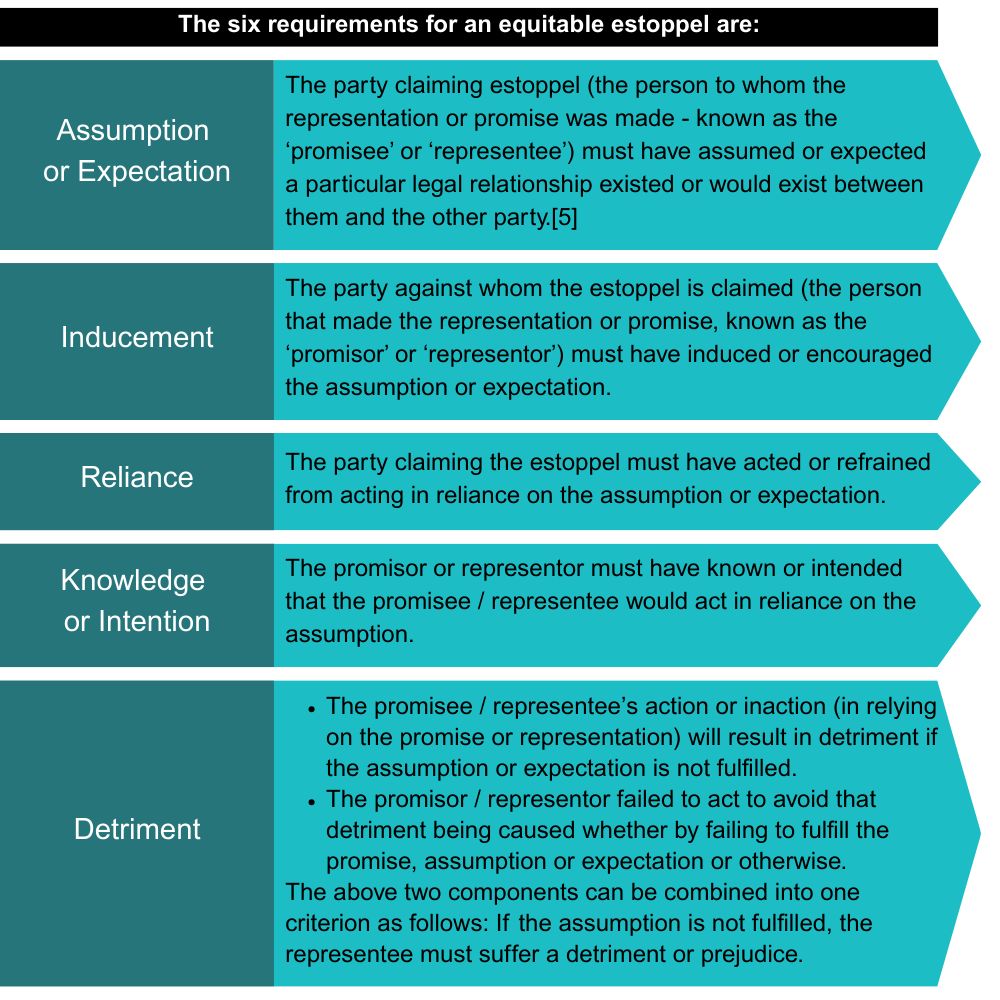

The High Court affirmed the long established legal ‘test’ for an equitable estoppel as stated by Justice Brennan in Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd v Maher (1988) 164 CLR 387 (Waltons Stores). [5]

In Kramer v Stone, the High Court confirmed that this test for establishing an estoppel is sufficiently general to include:

- estoppel by encouragement: an equitable estoppel which arises by reason of encouragement by the making of a promise; and

- estoppel by acquiescence: an equitable estoppel which arises by reason of acquiescence.

The different categories of estoppel

An estoppel arising from a promise upon which a person claims an entitlement to new property rights (such as a conveyance of land or “trust”) has been described as promissory estoppel, proprietary estoppel or, more generally, as estoppel by conduct and equitable estoppel.

The High Court considered there was no need in the Kramer v Stone appeal to consider whether there is any difference between these descriptions or if there is any “single overarching doctrine” of estoppel.[6]

In the appeal to the High Court, the parties agreed that the category of estoppel in issue should be described as “proprietary estoppel by encouragement”.

The High Court accepted that term is understood to refer to an estoppel which affords relief in equity “found in an assumption as to the future acquisition of ownership of property … induced by representations upon which there had been detrimental reliance by the plaintiff” and which arises in the circumstances of this case solely by reason of detrimental reliance on a promise of a future conferral of a proprietary interest in land.[7]

The High Court made clear that the case did not call for consideration of whether, or when, any doctrine exists that might permit the creation of rights through any broader form of “estoppel by encouragement”.

The grounds of appeal

The appellants' grounds of appeal sought to add two additional requirements to an equitable estoppel that arises by encouragement, being:

- subsequent encouragement by the promisor; and

- actual knowledge by the promisor of the promisee’s reliance.

To support their arguments and contest the farm worker’s claim, the deceased estate tried to argue the application of other equitable principles:

Failed gifts

The appellants relied on the decisions of Corin v Patton,[8] Olsson v Dyson,[9] and Riches v Hogben[10] as authority to support their argument that proprietary estoppel by encouragement requires subsequent encouragement by the promisor.

These cases concern the circumstances in which equity is said to perfect an imperfect gift. As such, the High Court stated it was not necessary to consider this authority because the equitable principle of the perfection of imperfect gifts is a separate and independent doctrine from equitable estoppel. The Court emphasised that reliance and detriment are not factors in perfecting an imperfect gift.[11]

Estoppel by acquiescence

The appellants also sought to ‘borrow’ from the principles of estoppel by acquiescence to support their argument that proprietary estoppel by encouragement requires the promisor to have actual knowledge of the promisee's reliance.

They argued that the need to establish ‘knowledge or intention’ for an estoppel to arise the criterion that requires “defendant knew or intended” meant the farm worker needed to demonstrate that the farm owner had actually known that he relied on her promise to his detriment (which was not the case).

The High Court disagreed.

The High Court relied on the generality of the test for equitable estoppel by Justice Brennan in Waltons Stores, which is sufficient to cover both estoppel by acquiescence and estoppel by encouragement but then went onto “disentangle the requirements of the two different equitable estoppels” and draw a distinction between the two.[12]

In doing so, the High Court cited:

- Justice Brennan in Waltons Stores, confirming that equitable estoppel could arise from:

“encouragement to adhere to an assumption or expectation already formed” or from acquiescence which is “the result of a party’s failure to object to the assumption or expectation on which the other party is known to be conducting [their] affairs”;[13] and

- Justice Leeming from the earlier Court of Appeal decision:

“Why should it be necessary not only to know that the defendant has encouraged the plaintiff to labour under a false belief, but also to know that the plaintiff has relied on the encouragement? The distinction is quite artificial.”[14]

Accordingly, estoppel by encouragement does not require the promisor to have actual knowledge that their promise (or representation or encouragement) has in fact been relied upon.

An overview of estoppel by encouragement and estoppel by acquiescence

Estoppel by encouragement v acquiescence

The main difference between an equitable estoppel arising by reason of encouragement by the making of a promise and an equitable estoppel arising by reason of acquiescence lies in the manner in which the estoppel is created and the representations involved.

An equitable estoppel arising by encouragement involves a clear and unequivocal promise made by the promisor to the promisee. A reasonable person in the promisor's position would expect that the promisee might rely on the promise by some act or omission, and the promisee must have relied upon the promise to their detriment. The promisee would suffer detriment if the promise was not fulfilled, leaving them in a worse position than if the promise had not been made. This form of estoppel does not require any further encouragement or actual knowledge of the acts of the promisee taken in reliance on the promise after the promise is made.

Estoppel by acquiescence has been described as a doctrine “which prevents a person, who has knowingly permitted another to act, through mistake, to his own detriment and to the advantage of the former, from profiting by the other’s mistake”.[15] When these elements are satisfied, an estoppel by acquiescence can be the source of new rights for the mistaken party.

The requirements for estoppel by acquiescence

The elements required for a person (“B”) to establish an estoppel by acquiescence against another (“A”) are:

- B must be mistaken as to their own legal rights;

- B must expend money, or do some act, on the faith of their mistaken belief;

- A must know of their own rights;

- A must know of B’s mistaken belief; and

- A must encourage B in [B’s] expenditure of money or other act, either directly or by abstaining from asserting [a] legal right.[16]

Accordingly, an estoppel claim can fail because A has no knowledge of B’s mistake and did not encourage B’s action.[17]

An equitable estoppel arising by acquiescence therefore does not necessarily involve a clear and unequivocal promise. Instead, it may arise from vague and imprecise conduct or representations that lead the promisee to adopt an assumption or expectation regarding future conduct. This type of estoppel can be created by the conduct of the promisor, including silence or passive behaviour, that leads the promisee to rely on the assumption to their detriment. The focus is on the promisor's conduct that would make it unconscionable for the promisor to depart from the assumption or expectation created in the mind of the promisee.

In summary, equitable estoppel by encouragement relies on a clear promise and subsequent detrimental reliance, whereas equitable estoppel by acquiescence can arise from vague representations and passive conduct leading to detrimental reliance.

The requirements for estoppel by encouragement

When the focus is only upon an equitable estoppel that arises by reason of encouragement from a promise, the elements that must be satisfied can be therefore refined as follows:

- a clear and unequivocal promise by the estopped party (the promisor) to the person who relies on the promise (the promisee) which will generally concern future conduct;[18]

- a reasonable person in the promisor’s position must have expected or intended that the promisee would rely upon the promise. This is what is meant by reference to the promise being an “encouragement” for the promisee to act;[19]

- the promisee must have relied upon the promise by acting or omitting to act in the general manner that would have been expected;[20] and

- the promisee will suffer detriment if the promise is not fulfilled, thereby leaving the promisee worse off than if the promise had not been made.[21]

The High Court determined that the elements of equitable estoppel were plainly satisfied in this case.

The decision

After considering the issues on appeal, the High Court found in favour of David, the farm worker, dismissing the appeal with costs.

Dissenting judgement

Justice Gleeson held the view that a voluntary promise will not generally give rise to an estoppel; rather, encouragement after a voluntary promise is what binds the promisor to that voluntary promise.[22]

As such, Justice Gleeson was of the view that the Court of Appeal made an error in finding an estoppel in the absence of conduct by Dame Leonie, after the promise was made, that encouraged David to act in reliance upon her promise.[23]

Takeaway

The decision provides an important clarity to the law of equitable estoppel: that equitable estoppel by encouragement does not require subsequent encouragement by the promisor or actual knowledge by the promisor of the promisee’s reliance.

The prospect of lifechanging inheritance often results in family disputes and contested probate cases where the validity and enforceability of wills are challenged, sometimes basing their inconsistency on earlier verbal promises.

If you were promised an inheritance, but not left what you were promised in a will, you may have grounds to enforce that promise. This may be the case even if the person who made the promise to you did nothing further to encourage you to rely upon it or did not know that you were relying on the promise.

If you would like any more information, please reach out to a member of our team.

-----

[1] [2024] HCA 48.

[2] Jesinta Burton WA Today, December 10, 2024: Not so happy families: Why WA’s looming intergenerational wealth transfer could be costly.

[3] [7], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[4] [11], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[5] Where it was expected that a particular legal relationship would exist between it is necessary to that the expectation be that the other party would not be free to withdraw from the expected legal relationship.

[6] [32], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[7] Ibid.

[8] (1990) 169 CLR 540.

[9] (1969) 120 CLR 365.

[10] (1985) 2 Qd R 292.

[11] [46], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[12] At [56] – [60].

[13] Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd v Maher (1988) 164 CLR 387 at 427.

[14] Kramer v Stone (2023) 112 NSWLR 564 at 622 [294] per Leeming J (Kirk JA agreeing).

[15] Discount & Finance Ltd v Gehrig’s NSW Wines Ltd (1940) 40 SR (NSW) 598 at 603 Jordan CJ. See also The New South Wales Trotting Club Ltd v The Council of the Municipality of the Glebe (1937) 37 SR (NSW) 288 at 308. Both cited at [54] by the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[16] [55], citing with approval the test set in Brand v Chris Building Co Pty Ltd [1957] VR 625 at 628.

[17] See Brand v Chris Building Co Pty Ltd [1957] VR 625 at 628.

[18] [37], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[19] [38], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[20] [39], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[21] [40], per the majority judgment of Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Beech-Jones JJ.

[22] [68], per the judgement of Gleeson J.

[23] Ibid.